May 17th, 2023

For the first time, scientists have devised a way to successfully extract human DNA from an ancient artifact — in this case, a 20,000-year-old deer-tooth pendant discovered in the famous Denisova Cave in southern Siberia.

The DNA extraction technique, which has been described as a non-destructive, high-temperature "washing machine," will make it possible to identify the biological sex and genetic heritage of the person who previously used or wore the item.

The breakthrough is credited to an international research team led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI) in Leipzig, Germany.

The team was able to determine that the deer tooth pendant was likely worn by a woman to lived between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago and was closely related to contemporaneous ancient individuals from further east in Siberia, the so called "Ancient North Eurasians."

The scientists explained that the woman's DNA had been transferred to the porous tooth pendant via skin cells or sweat. From the DNA retrieved they were able to reconstruct a precise genetic profile of the woman who used or wore the pendant, as well as of the deer from which the tooth was taken.

“For the first time, we can link an object to individuals,” Marie Soressi, an archaeologist from the University of Leiden, told newscientist.com. “So, for example, were bone needles made and used by only women, or also men? Were those bone-tipped spears made and used only by men, or also by women? With this new technique, we can finally start talking about that and investigating the roles of individuals according to their biological sex or their genetic identity and family relationships.”

What's amazing about the new DNA extraction technique is that it leaves the specimen fully intact.

The team tested the influence of various chemicals on the surface structure of archaeological bone and tooth pieces and developed a non-destructive phosphate-based method for DNA extraction.

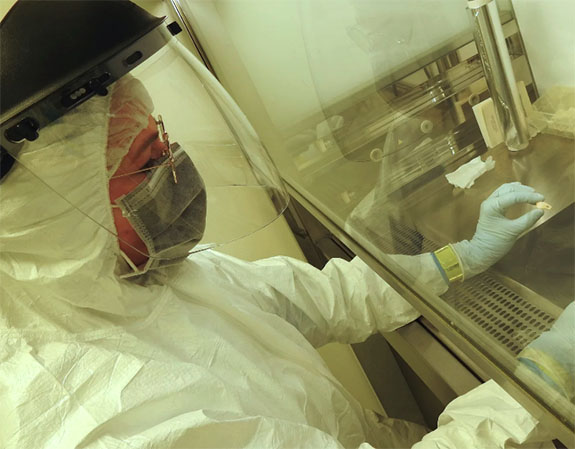

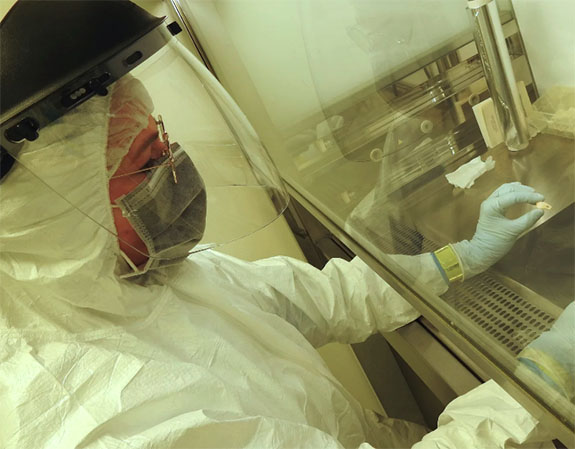

“One could say we have created a washing machine for ancient artifacts within our clean laboratory," explained Elena Essel, who developed the method and is the lead author of the study. "By washing the artifacts at temperatures of up to 90°C (194°F), we are able to extract DNA from the wash waters, while keeping the artifacts intact.”

In testing their methods, the MPI team had to overcome some frustration hurdles. For one, the artifacts had to be untouched by modern researchers, otherwise their own DNA would be on the items.

To overcome the problem of modern human contamination, the researchers focused on material that had been freshly excavated using gloves and face masks and put into clean plastic bags with sediment still attached, according to an MPI press release.

The breakthrough occurred when Maxim Kozlikin and Michael Shunkov — archaeologists excavating the famous Denisova Cave in Russia — cleanly excavated and set aside an Upper Paleolithic deer tooth pendant.

Utilizing that pristine artifact, the geneticists in Leipzig isolated not only the DNA from the animal itself, a wapiti deer, but also large quantities of ancient human DNA.

“Forensic scientists will not be surprised that human DNA can be isolated from an object that has been handled a lot,” said Max Planck geneticist Matthias Meyer, “but it is amazing that this is still possible after 20,000 years.”

Credits: Images courtesy of © MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The DNA extraction technique, which has been described as a non-destructive, high-temperature "washing machine," will make it possible to identify the biological sex and genetic heritage of the person who previously used or wore the item.

The breakthrough is credited to an international research team led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI) in Leipzig, Germany.

The team was able to determine that the deer tooth pendant was likely worn by a woman to lived between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago and was closely related to contemporaneous ancient individuals from further east in Siberia, the so called "Ancient North Eurasians."

The scientists explained that the woman's DNA had been transferred to the porous tooth pendant via skin cells or sweat. From the DNA retrieved they were able to reconstruct a precise genetic profile of the woman who used or wore the pendant, as well as of the deer from which the tooth was taken.

“For the first time, we can link an object to individuals,” Marie Soressi, an archaeologist from the University of Leiden, told newscientist.com. “So, for example, were bone needles made and used by only women, or also men? Were those bone-tipped spears made and used only by men, or also by women? With this new technique, we can finally start talking about that and investigating the roles of individuals according to their biological sex or their genetic identity and family relationships.”

What's amazing about the new DNA extraction technique is that it leaves the specimen fully intact.

The team tested the influence of various chemicals on the surface structure of archaeological bone and tooth pieces and developed a non-destructive phosphate-based method for DNA extraction.

“One could say we have created a washing machine for ancient artifacts within our clean laboratory," explained Elena Essel, who developed the method and is the lead author of the study. "By washing the artifacts at temperatures of up to 90°C (194°F), we are able to extract DNA from the wash waters, while keeping the artifacts intact.”

In testing their methods, the MPI team had to overcome some frustration hurdles. For one, the artifacts had to be untouched by modern researchers, otherwise their own DNA would be on the items.

To overcome the problem of modern human contamination, the researchers focused on material that had been freshly excavated using gloves and face masks and put into clean plastic bags with sediment still attached, according to an MPI press release.

The breakthrough occurred when Maxim Kozlikin and Michael Shunkov — archaeologists excavating the famous Denisova Cave in Russia — cleanly excavated and set aside an Upper Paleolithic deer tooth pendant.

Utilizing that pristine artifact, the geneticists in Leipzig isolated not only the DNA from the animal itself, a wapiti deer, but also large quantities of ancient human DNA.

“Forensic scientists will not be surprised that human DNA can be isolated from an object that has been handled a lot,” said Max Planck geneticist Matthias Meyer, “but it is amazing that this is still possible after 20,000 years.”

Credits: Images courtesy of © MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology.